Abstract

The engineering of “great beats”—rhythmic structures that elicit profound physiological entrainment and emotional resonance—has transitioned from an art form rooted in intuition to a quantifiable science situated at the intersection of digital signal processing (DSP), cognitive neuroscience, and computational musicology. We deconstruct the “groove” phenomenon through the lens of micro-temporal deviations and stochastic error models, determining the statistical properties that differentiate “human” feel from machine quantization. We further explore the neurobiological foundations of beat perception using the Kuramoto model of coupled oscillators to explain neural synchronization. The report extends into the spectral domain, applying the ISO 226:2003 equal-loudness standards and Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) to optimize emotional impact. Finally, we leverage recent advances in “Hit Song Science,” utilizing Random Forest classifiers and information-theoretic models (IDyOM) to predict the popularity and valence of rhythmic compositions. This document serves as a comprehensive, mathematically rigorous guide to reverse-engineering the emotional code of music. For producers who want to move beyond theory and actually test these timing models, the BTR music ecosystem includes curated libraries of hip hop and trap beats that are ideal for experimenting with swing ratios, micro-timing deviations and groove perception in real DAW sessions.

1. The Temporal Continuum: Micro-timing, Quantization, and the Mathematics of “Groove”

The perception of a “beat” is fundamentally a measurement of time. While Western music theory traditionally maps rhythm onto a discrete integer grid (quarter notes, eighth notes), the phenomenological experience of “groove”—the compulsion to move in response to auditory stimuli—exists in the continuous domain of milliseconds. The creation of a compelling rhythm requires the precise manipulation of these continuous values against the discrete expectation of the listener.

1.1 The Mathematics of Swing: Beyond the Grid

In the domain of electronic music production and drumming, “swing” is the systematic displacement of the weak metric subdivision (the off-beat) relative to the strong beat (the downbeat).In a standard 4/4 meter divided into eighth notes, a “straight” rhythm divides the quarter-note beat duration $T_{beat}$ into two equal halves. The “swing” phenomenon alters this ratio, creating a lilt that mimics the triplet feel of jazz or the loose pocket of funk.

The Swing Ratio ($S$) is mathematically defined as the percentage of the beat duration occupied by the first subdivision .

Where:

- d1 is the duration of the on-beat eighth note.

- d2 is the duration of the off-beat eighth note.

- d1 + d2 = T_beat (the total duration of the beat).

Historically, the Akai MPC sampler series (specifically the MPC60 and MPC3000) codified this parameter, establishing a standard that largely defines modern hip-hop and electronic dance music (EDM). The “MPC Swing” settings provide a discrete set of ratios that have become culturally embedded standards.

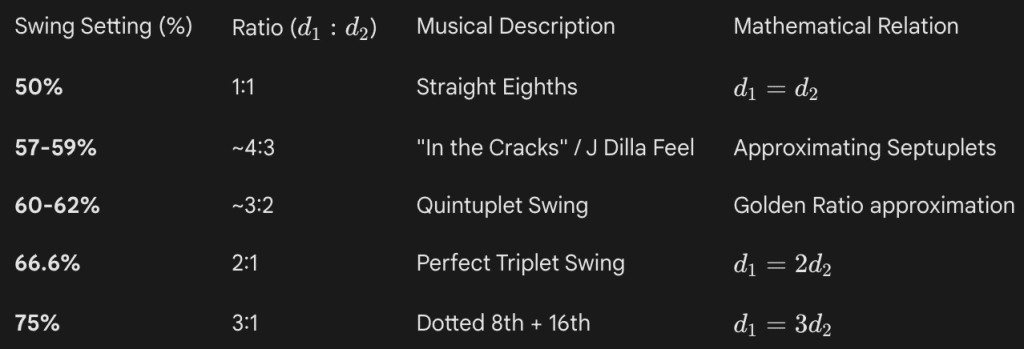

Table 1: Standard Swing Ratios and their Musical Correlates

Data derived from analysis of MPC timing architecture.1

Research into the micro-timing of jazz and funk performances reveals that human musicians rarely adhere to a static swing ratio. Instead, the ratio $S$ is a dynamic variable $S(t, v)$, dependent on tempo ($t$) and performance velocity ($v$). At faster tempos (e.g., >200 BPM), the swing ratio typically compresses toward 50% (straight) because the physical limitation of limb movement makes maintaining a high 2:1 ratio difficult. Conversely, at slower tempos, the ratio can expand. The “MPC feel” revered in hip-hop production often utilizes values like 57% or 61%, which do not align with standard Western tuplets.1 These “irrational” ratios create a rhythmic friction—a cognitive dissonance between the brain’s expectation of a grid and the auditory reality—that is resolved through physical movement (head nodding).

1.2 Micro-timing Deviations (MTD) and Participatory Discrepancies

A central debate in music psychology concerns the necessity of Micro-timing Deviations (MTDs) for the sensation of groove. This debate contrasts the “Exactitude” hypothesis (that perfect timing yields the best groove) with Charles Keil’s theory of Participatory Discrepancies (PD). PD theory posits that it is the imperfections—the slight asynchronies between bass and drums, or between the metronome and the player—that invite the listener to “participate” in the rhythm construction.

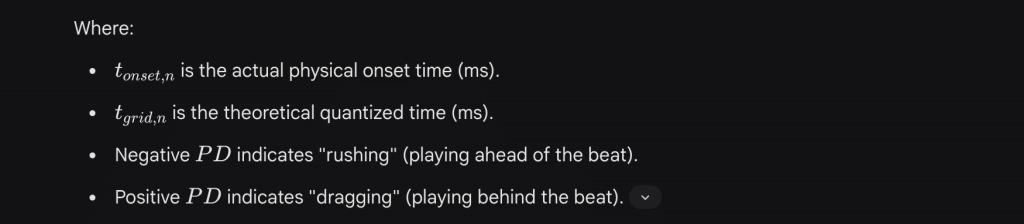

To quantify this, researchers measure the Phase Difference (PD) of onsets relative to a metronomic grid. For a sequence of N events, the deviation of the n-th event is:

Empirical studies challenging PD theory have yielded nuanced results. In controlled listening experiments, bass and drum patterns were manipulated to have varying magnitudes of MTD, scaled from 0% (perfectly quantized) to 100% (original human performance) and even 200% (exaggerated). Listeners, both expert and non-expert, did not universally prefer the humanized versions. In funk genres, quantization often did not degrade the groove rating, and in some contexts, the “tightness” of 0% deviation was preferred over the original human performance.

This suggests a specific psychoacoustic window for MTDs. While gross errors are rejected as “sloppy,” extremely subtle deviations (e.g., <10ms) may be imperceptible as timing errors but contribute to the “texture” or “width” of the beat. The “pocket” in drumming—often defined as a snare drum hitting slightly late relative to the kick—is a systematic, not random, deviation.

1.3 Stochastic Models: Gaussian vs. 1/f Noise

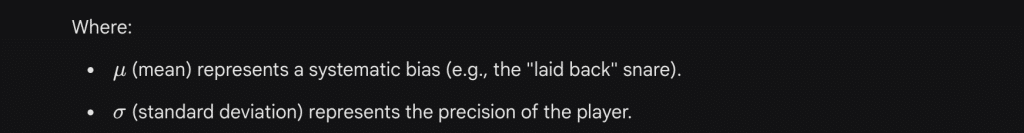

When digital audio workstations (DAWs) attempt to simulate “human feel” via a “Humanize” function, they typically employ a Gaussian (Normal) distribution to generate random timing offsets.

The probability density function for a timing offset x is given by:

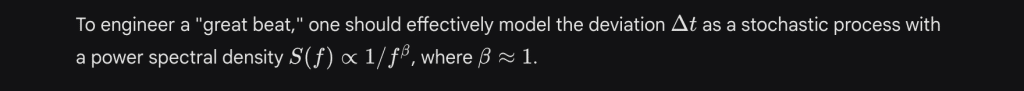

However, analysis of professional drummers (e.g., Jeff Porcaro, Clyde Stubblefield) reveals that their timing fluctuations are not random white noise (uncorrelated). Instead, they exhibit $1/f$ noise (pink noise), also known as fractal noise. This implies a long-range correlation structure: if a drummer plays slightly ahead of the beat now, they are statistically likely to continue that trend for a duration before correcting. This “autocorrelated” error sounds organic and cohesive to the human brain, whereas the white noise generated by standard DAW randomizers sounds “jittery” or disconnected.

1.4 Syncopation and the Longuet-Higgins & Lee Index

If micro-timing is the texture of groove, syncopation is the structure. Syncopation acts as a mechanism of tension, contradicting the listener’s metric expectations. The Longuet-Higgins and Lee (LHL) algorithm provides a robust computational index for quantifying syncopation based on metric hierarchies.

The LHL model assigns a Metric Weight ($W$) to each position in a measure. For a 4/4 bar:

- Downbeat (Beat 1): W=0 (Strongest)

- Beat 3: W=1

- Beats 2, 4: W=2

- Eighth notes (off-beats): W=3

- Sixteenth notes: W=4

A syncopation occurs when a note exists at a weaker metric level (higher $W$) without a subsequent note at a stronger metric level (lower $W$). The Syncopation Index ($S_{index}$) is the sum of the weight differences for all syncopated pairs:

Research demonstrates an Inverted-U relationship (Wundt Curve) between syncopation and groove.

- Low Syncopation: (e.g., a marching band beat). Predictable, but low groove ratings.

- High Syncopation: (e.g., complex math-metal or free jazz). Chaotic, difficult to entrain to, low groove ratings.

- Moderate Syncopation: The “sweet spot.” Sufficient complexity to engage predictive coding mechanisms, but enough regularity to maintain the pulse. This range maximizes the “desire to move”.

2. The Neuroscience of Entrainment: Why We Sync

The phenomenon of a “great beat” is not merely an aesthetic judgment; it is a biological event characterized by Neural Entrainment. This is the process by which the firing rates of neural populations synchronize with the periodicity of an external auditory stimulus.

2.1 The Kuramoto Model of Coupled Oscillators

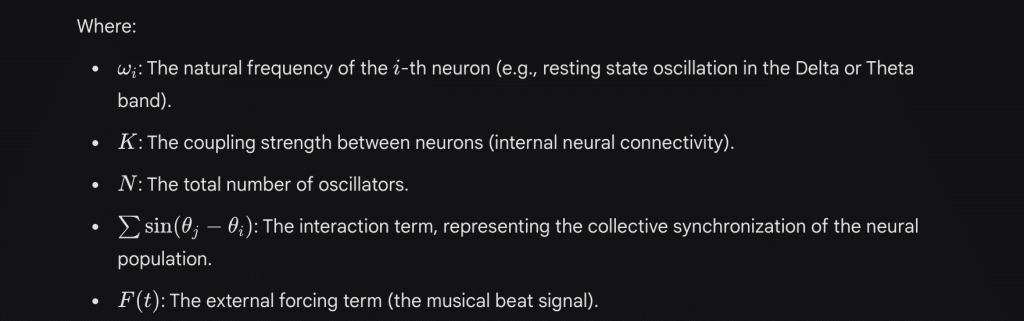

To model the interaction between a musical rhythm and the human brain, we utilize the Kuramoto Model, a canonical mathematical framework for describing the synchronization of coupled oscillators.In this context, we model neural populations (e.g., in the auditory cortex and motor planning areas) as oscillators with natural frequencies, and the musical beat as an external periodic forcing term.

The governing differential equation for the phase theta_i of the i-th neural oscillator is:

The system’s degree of synchronization is measured by the complex Order Parameter (r):

If r approx 0: The oscillators are phase-incoherent (no entrainment). The listener feels no groove.

If r approx 1: The oscillators are phase-locked to the beat (strong entrainment). The listener taps their foot.

For a beat to be effective, the forcing term $F(t)$ must be strong enough to overcome the variance in natural frequencies $\omega_i$. A distinct, high-transient beat (like a techno kick drum) provides a high-amplitude $F(t)$, forcing rapid phase-locking. This explains why dance music prioritizes transient clarity—it mathematically maximizes the Kuramoto order parameter in the listener’s brain.

2.2 Oscillatory Bands and Motor Coupling

- Delta Band (1–4 Hz): Entrains to the primary beat (tempo).

- Theta Band (4–8 Hz): Entrains to the meter (bar level).

- Beta Band (12–30 Hz): Entrains to subdivisions (eighth/sixteenth notes) and is critical for predictive timing.

A “great beat” establishes a hierarchical signal that stimulates these bands simultaneously. The kick drum drives the Delta band, the snare/claps delineate the Theta cycle, and the hi-hats stimulate Beta activity. This multi-spectral entrainment recruits the basal ganglia and supplementary motor area (SMA), creating the involuntary motor response known as “groove.” Even when a listener is stationary, the motor cortex is active, simulating the movement—a phenomenon known as “action simulation”.

2.3 Dopaminergic Reward and Prediction Error

The emotional “high” of music is chemically mediated by dopamine release in the Striatum (specifically the Nucleus Accumbens). This release follows the Reward Prediction Error (RPE) principle. The brain is a predictive machine, constantly generating probabilistic models of the next auditory event.

- Dorsal Striatum: Active during the anticipation of a peak.

- Ventral Striatum: Active during the experience of the peak (the reward).

If a beat is 100% predictable (zero entropy), the RPE is zero, and no dopamine is released (habituation). If the beat is random (maximum entropy), predictions fail, leading to frustration. The “great beat” balances on the edge of uncertainty. A syncopated accent or a sudden “drop” constitutes a Positive Prediction Error—the music did something better or more interesting than the baseline model predicted, triggering a dopamine spike.

Pharmacological studies confirm this causal link: participants administered Levodopa (a dopamine precursor) reported higher pleasure and stronger urge to move to music compared to a placebo group, while those given Risperidone (a dopamine antagonist) showed reduced sensitivity to musical pleasure.

3. Probabilistic Modeling of Musical Surprise: The IDyOM Framework

To mathematically quantify the “surprise” that drives dopamine, we turn to the Information Dynamics of Music (IDyOM) framework. IDyOM is a variable-order Markov model that analyzes musical sequences to calculate the information-theoretic properties of each event. It allows data scientists to predict which notes or rhythmic hits will generate the highest cognitive load and emotional response.

3.1 Information Content (Surprisal)

The core metric of IDyOM is Information Content (IC), often referred to as “surprisal.” It is the negative logarithm of the conditional probability of an event $e_i$ given its preceding context:

- Low IC (e.g., 1-2 bits): The event was highly expected (e.g., a kick drum on beat 1).

- High IC (e.g., >8 bits): The event was unexpected (e.g., a silence where a drop was expected, or a snare on an erratic subdivision).

3.2 Entropy and Uncertainty

While IC measures the surprise of an outcome, Entropy ($H$) measures the uncertainty of the context before the event occurs.

Where $A$ is the “alphabet” of possible musical events (e.g., all possible rhythmic values).

Recent EEG research indicates that Beta and Gamma band power in the frontal cortex are positively correlated with the IC of the music. This provides a direct translation layer:

$$ \text{Music Statistics (IC)} \rightarrow \text{Neural Oscillation (Beta/Gamma)} \rightarrow \text{Subjective Pleasure} $$

3.3 n-Gram Models and Smoothing

To calculate these probabilities, IDyOM utilizes n-gram models, which analyze sequences of length n.

- A 1-gram model looks only at the global frequency of notes (0th order).

- A 3-gram model predicts the next note based on the previous two.

Since musical sequences are sparse (many possible sequences never occur), the model employs Smoothing techniques like Prediction by Partial Matching (PPM) to blend probabilities from different order models.

Where $\lambda_n$ represents the weighting of the $n$-order model. This mathematical “back-off” strategy mirrors human cognition: we rely on immediate short-term memory (high-order n-grams) but fall back on general genre expectations (low-order n-grams) when the immediate context is novel.

Data scientists can use these models to “score” a generated beat. A beat with a flat IC profile is boring. A beat with a dynamic IC profile—periods of low entropy (groove establishment) punctuated by spikes of high IC (fills/variations)—optimizes the reward function.

4. Spectral Engineering and Psychoacoustics: The Physics of Impact

While rhythm dictates when energy occurs, spectral content determines how that energy physically impacts the listener. Creating a “great beat” requires exploiting the non-linearities of the human auditory system.

4.1 ISO 226:2003 Equal Loudness Contours

The human ear is not a linear transducer. It exhibits frequency-dependent sensitivity, described by the Fletcher-Munson curves, now standardized as ISO 226:2003. These contours map the Sound Pressure Level (SPL) required for a tone to be perceived as equally loud across the spectrum.

Crucially, the ear is massively insensitive to low frequencies. At 20 Hz, a sound must be ~75 dB SPL to be barely audible (the threshold of hearing), whereas at 3 kHz, the threshold is near -5 dB SPL.

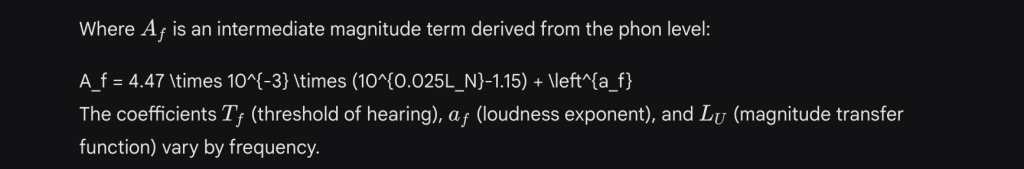

The standard calculation for the Phon level (LN) from SPL (Lp) at frequency f involves the following derivation:

Table 2: Selected ISO 226:2003 Coefficients

| Frequency (f) [Hz] | Exponent (af) | Transfer Mag (LU) | Threshold (Tf) |

| 31.5 | 0.480 | -23.0 | 59.5 |

| 63 | 0.409 | -13.0 | 37.5 |

| 125 | 0.349 | -6.2 | 22.1 |

| 1000 | 0.250 | 0.0 | 2.4 |

| 4000 | 0.242 | 1.2 | -5.4 |

Data Source: ISO 226:2003 Standard.

Implication for Beat Production: To make a kick drum (fundamental ~50-60Hz) sound as loud as a snare (fundamental ~200Hz) or vocal (1-3kHz), it must carry significantly more physical energy. This explains the “Smile Curve” in mastering: boosting lows and highs to compensate for the ear’s mid-range focus. It also dictates that “great beats” must allocate the majority of their headroom (dynamic range) to the low end, as this frequency band requires the most power to achieve perceptual parity.

4.2 Spectral Centroid and Timbral Brightness

The Spectral Centroid is the “center of mass” of the spectrum and serves as the primary predictor of perceptual “brightness.”

Where $x(n)$ is the magnitude of the frequency bin $n$, and $f(n)$ is the center frequency.30

- High Centroid: Associated with high arousal, tension, and energy (e.g., risers, white noise sweeps, distorted synths).

- Low Centroid: Associated with low arousal, warmth, and relaxation (e.g., sub-bass, filtered pads).

Dynamic manipulation of the spectral centroid—such as a Low Pass Filter (LPF) opening up over 8 bars—is a standard technique in EDM to mathematically ramp up the energy arousal of the crowd before a drop (For implementation details of spectral descriptors, see also Spectral Centroid in MATLAB & Simulink.)

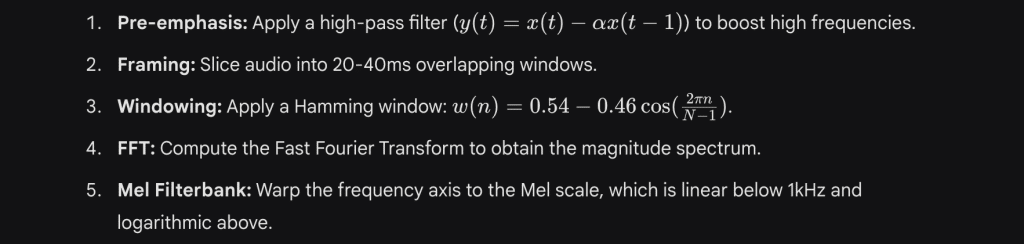

4.3 Feature Extraction: Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs)

To analyze the timbre of beats using machine learning, we employ MFCCs, which compress the spectrum into a set of coefficients that approximate the human auditory response. The calculation pipeline is rigorous:

- Logarithm: Take the log of the filterbank energies (simulating decibel perception).

- DCT: Apply the Discrete Cosine Transform to decorrelate the coefficients.

The resulting coefficients (usually 13-20) form a vector that describes the “timbral shape” of the beat. In “Hit Song Science,” the first coefficient (MFCC1) often correlates with the overall energy/loudness, while MFCC2 and MFCC3 correlate with the spectral balance (bass vs. treble). For a foundational overview, see also Mel-frequency cepstrum.

4.4 The Mathematics of Compression and Harmonic Distortion

To achieve the density characteristic of modern “great beats,” engineers utilize Dynamic Range Compression (DRC). A compressor is an automated gain control system defined by a transfer function.

For a “Soft Knee” compressor (preferred for musicality), the output level $Y_{dB}$ is calculated from input $X_{dB}$:

Where:

- $T$: Threshold (dB)

- $R$: Ratio (input:output)

- $W$: Knee Width (dB).

The Hidden Role of Distortion:

When attack and release times are extremely fast (< 20ms), the compressor tracks the individual waveform cycles of low-frequency sounds (e.g., bass at 50Hz = 20ms period). This modifies the wave shape, introducing Harmonic Distortion. While technically an error, this distortion adds upper harmonics to the bass signal. According to the Missing Fundamental psychoacoustic phenomenon, these harmonics allow the brain to perceive the bass note even on small speakers (like phones) that cannot physically reproduce the fundamental frequency. Thus, “saturation” is not just an effect; it is a psychoacoustic optimization tool. In practice, many of these spectral and dynamic-range decisions can be offloaded to an intelligent chain such as the AI mastering engine, which is tuned for rap, trap and R&B and explicitly optimises loudness, low-end headroom and spectral balance so kicks, snares and subs hit the psychoacoustic sweet spot on phones, headphones and club systems.

5. Data Science in Music: Predicting Hits and Valence

We can now move from the physics of a single beat to the statistical analysis of millions of songs. Hit Song Science employs supervised machine learning to predict chart success and emotional valence.

5.1 Feature Importance using Random Forests

Recent studies analyzing Spotify and Billboard datasets utilize Random Forest Classifiers and Logistic Regression to identify the acoustic features that differentiate “Hits” from “Non-Hits.” These models typically achieve prediction accuracies between 82% and 89%.

The feature importance rankings from these models provide a recipe for commercial success.

Table 3: Feature Importance for Hit Prediction (Normalized Impact)

| Feature | Importance Rank | Definition | Trend in Hits |

| Loudness | 1 | Integrated LUFS | Higher is better (up to -5 LUFS) |

| Danceability | 2 | Beat regularity & strength | High (stable tempo, strong transients) |

| Energy | 3 | Intensity (RMS + Centroid) | High |

| Valence | 4 | Musical Positivity | Variable (Current trend toward lower valence/sad bangers) |

| Duration | 5 | Length (ms) | Shorter is significantly better (< 3:30) |

Data aggregated from.39

The dominance of Loudness and Danceability confirms the importance of the DSP techniques discussed in Section 4 (Compression) and Section 2 (Entrainment). A track that is not loud enough (failing to saturate the ISO 226 curves) or lacks danceability (failing to drive the Kuramoto oscillators) is statistically unlikely to succeed. On the analysis side, tools like the Song Key & BPM Finder expose many of the same features used in hit-prediction research—tempo, key, Camelot position, energy and danceability—making it trivial to benchmark a new beat’s statistical profile against the grooves that are already working in the wild.

5.2 Emotional Valence Prediction

Predicting the emotional content (Valence and Arousal) of a beat is a regression problem. Studies utilizing the Valence-Arousal-Dominance (VAD) model show that:

- Valence (Positivity) is predicted by: Mode (Major/Minor), Spectral Regularity, and Consonance.

- Arousal (Intensity) is predicted by: RMS Amplitude, Attack Time (ADSR), and Spectral Centroid.

Using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) on Mel-Spectrograms, researchers can predict these values with high correlation ($R^2 > 0.6$). Interestingly, models trained on “mixed” audio (all instruments together) outperform models trained on isolated stems, suggesting that the interaction between elements (the “mix”) carries more emotional information than the sum of the parts.

6. Case Study: The Science of “Weightless”

To illustrate the application of these principles in a therapeutic context, we analyze “Weightless” by Marconi Union, a track engineered specifically to reduce anxiety.

6.1 The Parameters of Relaxation

The composition of “Weightless” was guided by sound therapists to target specific physiological responses:

- Tempo Deceleration: The track begins at 60 BPM and gradually slows to 50 BPM. This targets the Entrainment of the listener’s heart rate and respiration, guiding them down to a resting state via the “frequency following response”.

- Harmonic Stasis: The track avoids repetitive rhythmic loops or sharp transitions. This keeps the Information Content (IC) low but prevents the formation of strong predictive models. By denying the brain a predictable grid, it prevents the engagement of the beta-band motor prediction systems, inducing a state of passive listening rather than active anticipation.

- Spectral Profile: Analysis shows a 1/f (Pink Noise) spectral distribution, mimicking natural soundscapes (wind, water). This fractal structure is known to be processed more efficiently by the auditory cortex than white noise or complex synthetic timbres.

6.2 Empirical Results

A study by Mindlab International reported that “Weightless” reduced overall anxiety by 65% in participants, outperforming tracks by Mozart, Enya, and Coldplay. Physiological measures showed significant reductions in cortisol (stress hormone), heart rate, and blood pressure.

However, scientific rigor requires noting that some comparative studies found “Weightless” to be effective but not statistically superior to other relaxing conditions (like silence) for all metrics (e.g., respiration rate), suggesting that the Placebo Effect and the listener’s expectation of relaxation also play a significant role.

7. Emotional Signal Processing: ADSR and the Envelope of Feeling

Finally, we examine how the shape of a sound—its ADSR Envelope—functions as an emotional signal.

- Attack (A): The time to reach peak amplitude.

- Decay (D): The time to drop to sustain level.

- Sustain (S): The constant amplitude during the note hold.

- Release (R): The fade out.

Research links envelope characteristics directly to the Arousal dimension of the circumplex model of emotion:

- Fast Attack (<10ms): Correlates with High Arousal, Fear, or Anger. It triggers the acoustic startle reflex.

- Slow Attack (>50ms): Correlates with Low Arousal, Sadness, or Relaxation. It bypasses the startle reflex.

In beat production, the “transient shaping” of drums is effectively emotional shaping. A snare with a transient shaper applied (increasing the attack spike) increases the “aggression” (Arousal) of the track not just by being louder, but by sharpening the time-domain gradient $dA/dt$.

8. Conclusion

The creation of a “great beat” is a quantifiable engineering challenge that requires the optimization of parameters across three distinct domains:

- The Temporal Domain: Utilizing Swing Ratios (ideally approximating 57-66%) and 1/f Micro-timing Deviations to maximize the Participatory Discrepancy without breaking the Kuramoto synchronization of the listener’s neural oscillators.

- The Spectral Domain: Shaping the frequency balance to conform to ISO 226 Equal Loudness Contours, ensuring the low-end energy drives physical entrainment while the Spectral Centroid and MFCCs communicate the intended valence.

- The Information Domain: Managing the Entropy and Surprisal (IC) of the rhythmic sequence (via IDyOM analysis) to maintain engagement without causing cognitive overload, thereby optimizing the Dopaminergic Reward Prediction Error signal.

For the modern data scientist or audio engineer, music is not magic; it is a high-dimensional signal processing problem where the “output” is human emotion. By rigorously applying these mathematical and biological models, we can reliably generate audio that positively affects hearing and generates positive emotion.

If you’re serious about building your sound and audience, start by exploring the BTR music ecosystem — from genre-specific hip hop, trap, afrobeats and drill music hubs to tools that help you actually release, promote and monetize your tracks. If you’re serious about engineering beats that perform in the real world, you can prototype ideas from this paper directly inside the BeatsToRapOn ecosystem: write over high-groove hip hop and trap beats, analyse tempo and harmonic context with the Song Key & BPM Finder, and finish your mixes through Valkyrie AI mastering to ensure the temporal, spectral and information-domain work you’ve done actually translates into loud, emotionally effective records.