Introduction

Generative AI music has advanced to the point where synthetic songs can closely mimic human compositions. This raises concerns for authenticity, copyright, and artistic integrity, driving the need for reliable detection systems. An AI music detector (or synthetic music forensics) is the emerging field dedicated to spotting “synthetic fingerprints” in audio by combining signal processing, machine learning, and digital forensics. Our goal is to design an ensemble-based detection framework that outputs a confidence index from 0 to 10, where 0 means definitely human-made, 5 indicates significant AI assistance, and 10 means fully AI-generated. This advanced system leverages multiple approaches in parallel – from traditional audio feature analysis to deep neural networks and even stem (track) splitting – to yield the most accurate classification of any type of music as human or AI-produced. With no resource constraints, we can employ robust models and extensive training data to “detect all AI” with high confidence.

Challenges in Identifying AI-Generated Music

Distinguishing AI-generated music from human performances is non-trivial because state-of-the-art models produce high-fidelity, stylistically diverse music. However, subtle telltale differences often exist:

- Spectral Artifacts & Timbre: AI audio may exhibit unnatural frequency artifacts or too-perfect timbral consistency. For example, generative models often use neural codecs/vocoders that can leave slight fingerprints (e.g. quantization noise or aliasing) in the spectrum. Human recordings might have analog noise, mic quirks, or variations in spectral content that AI lacks. Metrics like Spectral Flatness (measuring noise-like vs tone-like content) and Spectral Rolloff (frequency below which most energy lies) are examined to catch these differences. An AI-generated track might have an overly “flat” spectrum in some bands (too even, lacking the rich tonal variance of live instruments) or an oddly abrupt cutoff in high frequencies.

- Consistency & Micro-Variation: Human performances typically contain small imperfections – subtle timing deviations, velocity (volume) variations for each note, and expressive changes. AI-generated music, in contrast, can be too consistent or “sterile.” Listeners often report AI drums/percussion sounding mechanically flat and perfectly quantized, or AI vocals lacking the nuanced dynamics of a human singer. For instance, AI voices tend to be more monotone and lack emotional nuance compared to human voices An AI guitar solo might have every note timed and tuned exactly on grid, whereas a human guitarist naturally varies timing and pitch. Such overly efficient precision (described as “sterile as a scalpel” by one observer) can be a red flag. Conversely, some AI systems may introduce bizarre fluctuations or glitches not typical in human music – e.g. sudden harmonic jumps or incoherent phrasing – which can also be detected via anomaly analysis.

- Lyric and Composition Tells: When lyrics or compositional structure are AI-generated, there might be semantic or structural oddities. Lyrics could be grammatically correct but oddly generic or contextually off. Musically, an AI might loop sections in a way a human producer wouldn’t, or modulate keys in an unnatural place. These aspects are harder to quantify automatically, but in a human-in-the-loop setting they contribute to suspicion. Our focus, however, is on automated audio-based detection rather than manual metadata/lyric analysis.

- Hybrid (AI-Assisted) Music: A particularly difficult scenario is AI-assisted music – e.g. a human artist uses AI to generate a baseline track then overdubs or edits it. Here, only parts of the song are synthetic. Detection must be fine-grained enough to identify partial AI usage. This means analyzing each stem (vocals, drums, instrumentation) separately for AI traits. A track might score in the mid-range (~5–7 on our index) if it’s a human-AI hybrid: for example, human vocals over an AI-generated backing track, or vice versa. Identifying these cases requires looking for localized AI signatures within the mix, not just treating the song as a monolithic whole.

Multi-Faceted Detection Framework

To address these challenges, we propose an ensemble of multiple detection methods working in concert. The system breaks the problem into several layers of analysis, each leveraging different strengths (some focus on specific audio features, others on learned patterns). By combining their outputs, we obtain a robust overall confidence score. The major components of the proposed system are:

- Audio Feature Extraction & Classical Analysis – We compute a rich set of handcrafted audio features known to differentiate real vs. AI music.

- Deep Learning Spectrogram Analysis – We employ neural networks (CNNs/Transformers) that learn to spot subtle artifacts in the audio’s time-frequency representation.

- Stem Separation & Targeted Sub-Analyzers – We split the song into stems (vocals, drums, bass, etc.) and apply specialized detectors (e.g. voice deepfake detectors on vocals, instrument authenticity checks on instrumentation).

- Ensemble Decision Fusion – The outputs from all detectors are aggregated (via a learned ensemble model) to produce a single 0–10 confidence index of AI involvement. The ensemble captures complementary cues from each subsystem, yielding higher accuracy than any individual method alone.

Below we delve into each component in detail.

1. Feature Extraction & Classical Analysis

One pillar of the system uses expert-designed audio features and traditional machine learning to flag AI-generated audio. This approach is inspired by tools like the Submithub AI Song Checker, which uses a Random Forest classifier over dozens of audio features We will calculate a comprehensive set of descriptors that capture timbral, harmonic, and rhythmic properties of the track. Key features include:

- Spectral/Timbre Features: Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs) summarize the audio spectrum in a way that correlates with timbre and pitch perception We also examine Spectral Centroid (the “center of mass” of the frequency spectrum) and Spectral Bandwidth (spread of frequencies) which often differ in AI tracks Spectral Contrast measures the energy difference between peaks and valleys in the spectrum (per frequency band), indicating how “defined” vs. “smeared” the sound is AI outputs sometimes have less dynamic spectral contrast due to smoothing by generative models, or conversely, certain frequency bands may be overly emphasized. Spectral Flatness (mentioned earlier) helps detect an overly noise-like spectrum characteristic of some generative processes. By evaluating these, we can catch unnatural tonal balance or lack of the subtle irregularities found in analog recordings.

- Harmonic Features: We use Chroma features to analyze harmonic content Chroma vectors indicate the intensity of each musical pitch class (C, C#, D, etc.) regardless of octave, revealing the harmonic structure of a piece. Unusual harmonic patterns or key inconsistencies might suggest algorithmic composition. For instance, if the music modulates in ways typical of AI (which might not follow conventional musical form) or uses chords that are harmonically inconsistent, the chroma profile combined with music theory rules can flag it. Additionally, tonal stability features (does the song stay in a well-defined key or wander unpredictably?) are considered.

- Rhythmic & Temporal Features: We analyze tempo consistency, beat placement, and rhythmic patterns. AI-generated music might either be perfectly locked to a grid or, if the model struggles, introduce off-beat anomalies that a skilled human drummer likely wouldn’t We measure the variance in inter-beat intervals (micro-timing): a human drummer or ensemble has slight groove fluctuations, whereas AI might quantize strictly (variance near zero) or produce erratic rhythm if glitching. We also examine dynamic range and amplitude envelope features – humans often introduce crescendos, swings in loudness, whereas some AI tracks may have a more uniform loudness (unless explicitly modeled otherwise). Features like attack-decay patterns per note (e.g. how consistently each note’s envelope shapes are) can hint if they were generated.

- Higher-Level Musical Features: Although harder to quantify, our system can include statistics like melodic contour complexity or note randomness. For example, we could measure the entropy of the melody’s pitch sequence or the repetitiveness of hooks. AI models might inadvertently loop a short melodic phrase more often than a human would. If lyrics are present, we might do a basic NLP sanity check (though lyrics alone are not a sure indicator, they can be weird in AI songs).

We feed all these engineered features into a classical machine learning model (or a set of them). A Random Forest or Gradient Boosted Trees ensemble is useful here, as it can handle mixed feature types and is interpretable. Such models can give a preliminary probability that the song is AI-generated by recognizing patterns in the feature values. For example, the Submithub checker’s Random Forest was trained on 21 features across spectral, temporal, and harmonic domains. Our system greatly expands this feature set and training data for higher accuracy. By itself, this feature-based module can catch obvious AI traits (e.g., suspicious spectral cues or abnormal rhythm statistics). However, it might miss more subtle deepfake audio that closely mimics human characteristics, so we augment it with deep learning in the next stage.

2. Deep Learning Spectrogram Analysis

Parallel to the feature-based analysis, we deploy advanced neural networks to learn complex patterns and artifacts directly from the audio waveform or spectrogram. Deep learning has proven extremely effective in audio deepfake detection, often surpassing manual features arxiv.org. Our approach uses multiple models operating on different representations:

Spectrogram CNNs: We convert audio into time–frequency representations (such as mel-spectrograms or STFT spectrograms) and feed them into convolutional neural networks. CNNs can automatically learn discriminative features (visual patterns in the spectrogram) that differentiate real vs. AI audio. For example, certain high-frequency noise textures or inconsistencies between harmonic components might be learned. Early work showed simple CNNs on spectrogram slices can exceed 99% accuracy in closed-set conditions. We leverage a state-of-the-art hybrid model like SpecTTTra (Spectro-Temporal Transformer) which combines convolution and transformer blocks to handle entire songs efficiently The transformer layers allow the model to capture long-range dependencies (song-level structure) that CNNs alone might miss. This helps in detecting if an entire arrangement or progression “feels” AI-composed, beyond just momentary spectral quirks.

Ensemble of Feature-Stream Networks: Rather than rely on a single network, we can ensemble multiple feature-streams for robustness. One cutting-edge design is to use different input feature types in parallel, then fuse them. For instance, a recent system processes MFCC, LFCC (Linear Frequency Cepstral Coefficients), and CQCC (Constant-Q Cepstral Coeff.) features each through separate CNN streams, then combines them These cepstral features each capture slightly different aspects of the audio spectrum (linear vs mel-scaled vs constant-Q frequency spacing). By using all three, the model can detect a wider range of anomalies – essentially casting a “wider net” for vocoder or generator artifacts. The outputs of each feature-specific network are merged (concatenated) and fed to a classifier (e.g. a fully-connected layer) that decides real vs fake. This multi-branch architecture has shown robust performance on voice spoofing benchmarks and is equally applicable to music.

llustration of a multi-feature deep model: The audio is converted into several spectral representations (MFCC, LFCC, CQCC in this example), each processed by a deep CNN (ResNeXt-based) to extract embeddings. These are then fused (concatenated) and passed to a classifier that outputs a probability of the audio being AI-generated. This kind of architecture leverages diverse feature inputs to improve detection accuracy, as demonstrated by its low error rates on challenging deepfake audio datasets sciencedirect.com.

Transformers and Pretrained Audio Models: In addition to CNNs, we incorporate transformer-based models and pre-trained networks for specialized feature extraction. A promising approach is the dual-stream encoder used in the recent CLAM (Contrastive Listening Audio Model) system. In our framework, one stream could be a music-trained encoder (capturing musical textures and style) and another a speech/audio-trained encoder (capturing general audio anomalies). For example, we can use a model like MERT (Music Embedding Representation Transformer, pre-trained on music) alongside wav2vec 2.0 (a speech representation model). Both are fed the audio; one focuses on musical coherence, the other on audio realism. By fusing their outputs (e.g. via cross-attention layers, the system learns to spot subtle inconsistencies between the musical content and the acoustic waveform. If a song has vocals, the lyrics and melody might be musically plausible (music encoder says “sounds like a real song”) but the timbre or inflection of the voice might ring false (speech encoder flags synthetic qualities). This cross-modal ensemble catches cases where each individual model might be fooled, but the combination reveals an AI artifact. In fact, such dual-stream architectures have set new state-of-the-art in synthetic music detection, significantly improving accuracy on challenging, diverse datasets

The deep learning module will output its own AI-likelihood score. For instance, a transformer might output a probability $p_{\text{AI}}$ that the track is AI-generated. The CNN ensemble might output a similar score. We will later combine these with the classical feature model’s output. But first, we enhance the system’s granularity through stem-level analysis.

3. Stem Separation and Targeted Analysis

To detect partial AI usage (scores in the 1–9 range on our index), it’s crucial to analyze individual components of the music. Stem separation uses AI audio processing to split a song into its constituent tracks: typically vocals, drums, bass, and other instruments. Modern source separation tools (like AI stem splitters) are quite effective, allowing us to isolate, say, the vocal track from the accompaniment. With stems, our system can apply bespoke detectors to each layer:

- Vocal Deepfake Detection: If the song contains vocals, we run a dedicated voice deepfake detector on the isolated vocal stem. This detector looks for traits specific to AI-generated voices: e.g. slightly robotic tone, lack of breath variability, unnatural vibrato, or artifacts in the high frequencies from vocoding. Research shows that including the background music context in analysis actually improves fake singing detection accuracy mdpi.com – presumably because an AI-generated vocal might fit the background a bit too perfectly or lack the natural clashing with accompaniment that live recordings have. We therefore consider the vocal in context as well. Our vocal detector could use a model like AASIST or RawNet2 (state-of-the-art in spoof speech detection) which has been adapted for singing voice deepfakes mdpi.com. It might analyze micro-pitch fluctuations, formant coherence, or the presence of typical singer idiosyncrasies. If the vocal is determined to be likely AI (e.g. a voice clone of a famous singer), that will heavily influence the overall song’s AI score (likely pushing it into the 7–10 range). Conversely, an authentic vocal with an AI-generated instrumental might be flagged by the next item.

- Instrumental Analysis: Each instrumental stem (drums, bass, etc.) can be analyzed for AI signs. We look at things like sample authenticity and performance dynamics. For drums: Are the velocities of hits too uniform? Human drummers have slight variations even in electronic music, whereas AI might make every snare hit exactly the same loudness unless explicitly modeled. Also, the drum sounds themselves might be too pristine or identical every measure – AI might lack the subtle variation in timbre that comes from a human hitting cymbals or drums at different spots. For melodic instruments (guitar, piano, etc.): Does the phrasing and timing feel human? Are there performance nuances like string noise, breath intakes (for wind instruments), subtle tempo rubato? Absence of these might hint at AI. We can engineer features per stem (similar to the global features but on isolated tracks). Additionally, a deep neural network could be trained on spectrograms of individual instrument tracks (real vs AI-generated instrument performances). For example, a guitar-specific model might catch if a solo sounds algorithmically generated (perhaps by detecting if note sequences follow a Markovian randomness rather than emotional phrasing). A simpler tell could be the lack of “imperfections” – e.g., no fret buzz, perfectly quantized arpeggios, or impossibly fast note runs that push beyond human ability (unless it’s a genre where that’s expected). Each instrument detector yields a probability of AI for that stem.

- Cross-Stem Consistency: Another benefit of stem analysis is checking the relationships between stems. In human-produced music, the interaction between vocals and accompaniment has organic qualities (e.g., a singer might slightly lag or lead the beat in an expressive way, or a band might adjust timing to the vocalist). AI-generated songs, especially if one model generates everything at once, might have too-perfect alignment or other global consistencies. By comparing timing and frequency content across stems, we can find anomalies. For instance, do the kick drum transients align eerily well with the bassline with zero variance? Does the vocal never ever overlap frequencies with the lead guitar (which could imply they were synthesized separately to avoid collision)? We can devise features measuring these cross-stem correlations. Dual-stream models like CLAM effectively do this by having separate encoders for vocal vs instrumental streams and checking for subtle mismatches Inspired by that, our system can include a cross-analysis that flags if the vocal stem and instrumental stem individually sound fine but their combination is too coherent or has unnatural phase relationships (e.g., phase alignment in a mix that’s unlikely if vocals were recorded over an instrumental). Such details are minute, but with no resource limit we can comb through them.

By performing stem-by-stem checks, the system can catch partial AI cases. For example, if only the instrumental backing is AI-generated, the instrumental stems (drums, etc.) will likely trigger high AI probabilities while the vocal stem triggers low AI probability. The ensemble can interpret this as “AI-assisted” (somewhere in the middle of our scale). Conversely, if all stems show strong AI traits, the confidence score will lean towards 10 (fully AI).

4. Ensemble Fusion and Confidence Scoring

The final stage merges all the evidence collected: the classical feature model’s output, the deep learning model(s)’ outputs, and the per-stem analysis results. We use a meta-classifier (which could be another machine learning model or a set of weighted rules) to integrate these signals. Since we have zero resource constraints, we can even employ a high-capacity model (like a small neural network) to learn the optimal combination of features and model outputs that best predicts AI-generated content. For instance, the meta-ensemble might learn that “if the vocal detector is very sure of AI and the global spectral model is moderately sure, output a high confidence of AI,” whereas “if only one subsystem is flagging AI but others are confident it’s human, output a lower overall score.” Ensemble methods are known to improve accuracy by leveraging the strengths of each component and canceling out individual weaknesses. In our case, the feature-based module might catch obvious spectral tells that the deep network overlooked, while the deep network catches complex patterns the RF can’t see – combining them yields a more accurate and robust result.

The output is a confidence index 0–10 reflecting the degree of AI involvement:

- 0: Definitively human-made. All detectors found no signs of AI (e.g., natural feature values, deep models confident it’s real). This is rare unless the music is live or analog with no digital tampering.

- 1–4: Likely human. Some minor quirks might overlap with AI patterns, but overall signals point to a human performance. Could include songs with very subtle AI use or just coincidental regularity.

- 5–6: Ambiguous or AI-assisted. The system detected certain AI-like features or segments, but others seem human. This might indicate a mix of human and AI contributions – for example, human vocals over an AI-generated beat, or a human-composed song that used AI tools for polish. The music has noticeable AI influence but not entirely AI-made.

- 7–9: Predominantly AI-generated. Multiple detectors converge on finding AI signatures. Perhaps the composition and many stems were AI-created, possibly with some minor human editing. The song sounds mostly AI – e.g. very clean production, a “too perfect” instrumental, etc.

- 10: Definitely AI-generated. Every analysis aspect screams AI: the statistical features deviate strongly from human norms, deep models confidently classify it as fake, vocals/instruments contain known AI artifacts. Essentially no doubt remains that the song was produced by generative algorithms with little to no human performance.

The confidence scoring could be calibrated by training on a labeled dataset of songs (with ground truth whether AI was used and to what extent). For example, we might assign labels like 0% AI, 50% AI, 100% AI for training, and the ensemble outputs a percentage which we map to 0–10 scale. Another approach is to produce two probabilities: one that the track is human, one that it’s AI, and interpret a mixed probability (e.g. 60% AI) as an intermediate score (around 6/10). Since we want the system to “detect all AI”, we would err on the side of caution – any non-zero AI evidence bumps the score upward. The ensemble can be tuned to minimize false negatives (undetected AI) while managing false positives through transparent reporting (more on that below).

Training and Validation

Achieving high accuracy with this ensemble requires extensive training data and rigorous validation. Fortunately, we assume unlimited resources, so we can assemble a massive, diverse dataset for training the detectors:

- We would include tens of thousands of real and AI-generated tracks across all genres. Datasets like Melody or Machine (MoM) arxiv.org arxiv.org with over 130k tracks (real, fully fake, and partially fake) are excellent for training and testing. Also, datasets like FakeMusicCaps (AI-generated music from text prompts) mdpi.com and SONICS (mix of Suno/Udio AI songs and real songs) provide a wide coverage of generative models By training on such corpora, our models learn both in-distribution and out-of-distribution examples (covering many AI generation techniques). We ensure a balanced mix of human vs AI examples, various genres, lengths, and production styles so that the detectors don’t become biased to one genre or fooled by spurious correlations.

- Feature Model Training: We train the Random Forest (or similar) on labeled data, possibly with synthesized features to represent “edge” cases. It will learn decision boundaries in the 20+ dimensional feature space separating real from AI. For example, it might learn that a combination of high spectral flatness + low dynamic range + perfectly even tempo strongly correlates with AI.

- Deep Model Training: The CNN/Transformer networks are trained using supervised learning on spectrograms or waveforms labeled real/AI. We likely use data augmentation (e.g. random time shifts, slight EQ changes) to prevent overfitting. Notably, we will incorporate common audio transformations during training to improve robustness. Research has found that naive models can fail when fakes are pitch-shifted, time-stretched, or recompressed with lossy codecs – essentially, a clever adversary could post-process AI music to evade detection. To counter this, we augment training samples with random pitch shifts, tempo changes, added noise, reverberation, MP3 compression artifacts, etc. The ensemble then learns to recognize AI even after such obfuscation. This augmentation-aware training is crucial for a “detect all AI” mandate, ensuring our system doesn’t get fooled by simple tricks. We also employ continual learning – as new AI music models emerge, we update the training set and retrain/finetune the detectors to recognize the latest generation techniques.

- Validation: We validate on holdout sets and challenging scenarios. One testing approach is an open-set evaluation: include AI songs from generator models that were not seen during training to ensure the system generalizes. The dual-stream and ensemble approach is expected to perform well even on unknown AI generators (indeed CLAM’s design specifically targets generalization to new generative methods). We also test hybrid songs (part real, part AI) to ensure the confidence scores align with partial usage. Metrics like accuracy, F1-score, and calibration (does a score of 8 truly correspond to ~80% AI content?) are computed. In state-of-the-art research, ensembles and multi-stream models have achieved high accuracy: e.g., over 92% F1 on challenging multi-generator benchmarks. We aim for similarly high performance, tweaking the ensemble weights as needed to reduce errors.

Despite our best efforts, no detector is perfect. As a final safeguard, if the system is deployed, we would include an option for manual review or explainable output. For any given song, the system can highlight which features or sections led to a high AI score (e.g., “the vocal timbre had a vocoder-like spectrum” or “the drum pattern was highly quantized”). Providing such explanation builds trust and allows human experts to verify borderline cases. This also helps avoid false accusations – for example, if a human-produced song is mistakenly flagged (perhaps due to an unusual style), the review might catch that and the model can be improved from that feedback.

The Methodology: Inside the BTR V8 Engine – Advanced & Most Accurate AI Music Detector

BTR V8 introduces a deterministic, multi-modal ensemble approach. Instead of relying on a single neural network, we decompose the audio signal into six distinct “forensic dimensions”—from sub-perceptual spectral artifacts to high-level rhythmic quantization. By fusing these independent signals through a non-linear gating mechanism, we achieve robust detection rates while minimizing false positives on high-fidelity organic recordings.

1. The Mathematical Framework

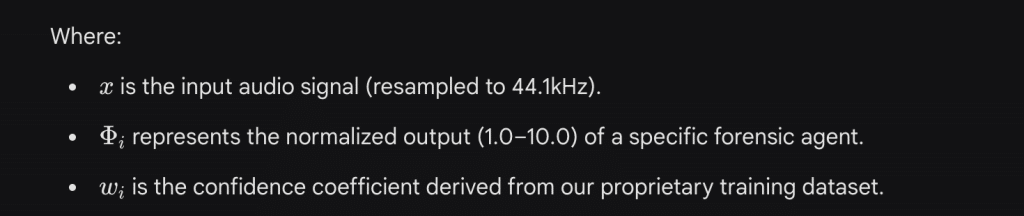

At its core, BTR V8 operates as a Weighted Logistic Ensemble. We treat the detection problem not as a singular question, but as a jury of six independent experts ($\Phi$), each analyzing a specific domain of the audio file.

The raw aggregate score is calculated via the weighted summation of these expert feature vectors:

To convert this raw forensic data into a probability, we employ a Sigmoid Activation Function with dynamic scaling. This ensures the model remains decisive, pushing ambiguous signals toward a clear classification unless the evidence is truly conflicting.

2. Feature Extraction Agents

Our system does not “listen” to music in the traditional sense. It dissects the physics of the sound wave. We employ six specialized agents:

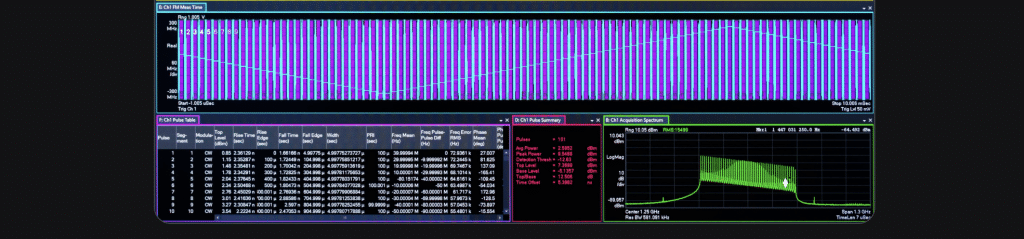

A. Spectral Artifact Analysis

Generative audio models (particularly latent diffusion models) often leave microscopic grid-like patterns in the frequency domain—fingerprints of the mathematical convolution layers used to generate the sound.

- Technique: We perform a Cepstral Analysis of the logarithmic magnitude spectrum.

- The Math: We calculate the Peak-to-Noise Ratio (PNR) within specific “queuing” frequency bands ($B_{grid}$).

- Logic: A human recording has a chaotic, organic noise floor. An AI recording often exhibits mathematically perfect “spikes” in the cepstrum where the grid aligns.

B. Phase Entropy & Physics

This is our “Safety Valve.” Real sound waves obey the laws of physics; they have complex phase relationships and natural stereo imaging. AI models often generate “naive” phase information.

- Technique: We extract the instantaneous frequency using the Hilbert Transform and compute the Shannon Entropy.

- The Insight: Organic recordings have high phase entropy (chaos). AI generations often have anomalously low entropy (mathematical purity) combined with high stereo coherence—a combination that rarely occurs in nature.

C. Rhythmic Quantization ($\Phi_{rhythm}$)

Human drummers, even when playing to a click track, have micro-deviations in timing (groove). AI models, unless specifically prompted otherwise, tend to snap transients to a perfect mathematical grid.

- Technique: We isolate the percussion stem and analyze the variance of Inter-Beat Intervals.

- Logic: If the variance approaches zero, the likelihood of synthetic generation increases exponentially.

D. Cross-Modal Consistency

In a real band, the bass player and drummer interact. In an AI model, different stems are often generated via separate attention heads, leading to subtle “gluing” errors.

- Technique: We compute the Normalized Cross-Correlation ($\rho$) between the vocal and drum envelopes.

- Logic: We flag two extremes:

- Zero Correlation: The vocals and drums feel like they belong to different songs.

- Hyper-Lock: The vocals and drums are mathematically phase-locked in a way that is physically impossible for human performers.

The Safety Valve: If the Physics Agent detects natural phase entropy, the system “vetoes” the other agents, capping the maximum AI probability at ~5%. This prevents high-quality electronic music (which is quantized and polished) from being falsely flagged as AI.

The Boost: Conversely, if the Fourier Agent detects distinct grid artifacts, the system boosts the final probability score, as these artifacts are considered a “smoking gun” for synthesis.

By combining signal processing theory with statistical analysis, BTR V8 moves beyond simple pattern recognition. It doesn’t just ask “Does this sound like AI?”; it asks “Does this file obey the laws of physics and human performance?”

This multi-dimensional approach provides a transparent, explainable, and robust defense against the increasing fidelity of generative audio.

Conclusion

Detecting AI-generated music requires a multi-pronged strategy. By combining traditional signal features (spectral, harmonic, rhythmic descriptors) with cutting-edge deep learning models and stem-specific analysis, we create a robust ensemble that evaluates music from every angle. This comprehensive system exploits the fact that while an AI-generated song might imitate many facets of human music, it’s extremely hard to fool all detectors simultaneously. Some module – be it the spectral analysis, the rhythmic irregularity check, or the vocal authenticity model – is likely to pick up the subtle artificial fingerprint left behind. The ensemble then consolidates these findings into a single intuitive score from 0 (no AI) to 10 (full AI). With unlimited computational resources, we can afford large training sets, powerful models, and extensive cross-validation, pushing detection accuracy to the maximum. The result is a high-confidence AI music detector that can flag everything from fully AI-composed pieces to those lightly touched-up by AI. Such a tool would be invaluable for musicians, platforms, and listeners in an age where the line between human and machine creativity is increasingly blurred. By continuously updating the system as AI models evolve, and by using an advanced composition of approaches, we can indeed inch closer to detecting all AI-generated music with a high degree of certainty